Thanks for taking a read. This one is longer than my usual. I apologize if it doesn’t all fit in your inbox, but if it doesn’t you can click through to my Substack to read it in its entirety for free. Happy Friday and I hope you have a great weekend.

My opinions shared in this essay are based upon my decades being and witnessing alcoholics and drug addicts. I give a brief, but factual history of the battle between prohibition and legalization of alcohol and schedule 1 narcotics. My perspective will always be based in whether I see any impact of this battle on addiction and the treatment of addiction.

Full disclaimer: I support the idea of decriminalizing drug use. Why? Because prohibition hasn’t worked. One definition of insanity is doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting a different result. Our society has more users using more often, more self-medication, more prescribed medication, more addicts, more availability, more alcohol and drug-related crime, more cartels, and more prisoners.

The Law does not enter into the mind of an addict. It isn’t the last thing on their mind—it isn’t even there.

Prohibition

Alcohol Prohibition came about in January 1919 with the eighteenth amendment to the US Constitution. Alcohol consumption had been an issue in America since Colonial times. There’s ample evidence that a few of our Founding Fathers were drunks. Taxes were imposed on liquor by the new Continental Congress which resulted in the whiskey rebellion of the late 1790s to help pay down the national debt.

Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican party wrested power from Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist Party in 1800 and repealed the whiskey tax. Based upon several state-run temperance societies, the American Temperance Society was formed in 1826 and it forged ahead with a temperance movement throughout the mid-1800s, pushing for prohibition of alcohol consumption and other in-temperate behaviors. This “dry crusade” reached a crescendo in 1881 with the state of Kansas becoming the first state to ban liquor consumption. A massive number of saloons opened across America in the post-Civil War period, timed with the industrial revolution and urbanization of the country. Religious organizations and churches vigorously opposed saloons and drinking in general during the period of 1890-1920 with the formation of the Anti-Saloon League.

Prohibition represented a clear battle between rural and urban America, with rural Americans blaming much of the immoral and indecent behavior in the cities on the wave of migrants flocking to urban centers for work. Economists at the time were increasingly in favor of prohibition, arguing that overconsumption in urban areas was hurting the attendance and work performance of many workers in the factories and plants that were springing up. “Blue Mondays” became the name for unproductive Mondays following a weekend of binge drinking. The prohibitionists changed tactics politically based upon this economic impact, pressing for the passing of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913, which created a federal income tax to supplant the alcohol taxes provided by alcohol sales that they so wanted to be rid of.

One of the key turning points in the fight for prohibition came when America declared war on Germany in April 1916. German Americans were among the staunchest opponents of prohibition, as they dominated a large part of the brewing industry and the saloon business. They were quickly diminished at the start of the war and the grain used for brewing was quickly re-assigned for export to support the war effort.

What were the results of alcohol Prohibition?

Prohibition took effect on January 17, 1920. The Volstead Act was the enforcement. Over 1,500 federal prohibition agents were commissioned nationwide as the enforcers. With the perspective of history, we know that the 13 years of prohibition was an abject failure and a disaster. Then and now, attempts to control human behavior through morality-based legislation does not work. America’s crime families exploded in revenue, growth in members, and in arms. Much of history’s most famous family wealth creation occurred as a result of prohibition. The upper class of the that period simply emptied or relocated the warehouses and saloons into their own personal hoards. Sitting President Woodrow Wilson and his successor Warren Harding both had copious stashes. I’ve personally toured the old brewery tunnels in the historic Soulard District of St. Louis that offered stealthy transport from the basement of the brewhouses to waiting boats and barges on the Mississippi.

In addition to the widespread bootlegging, alley speakeasys, and a general snubbing of the law by the monied set; there was also the cold hard reality for the working class in America who were forced to imbibe whatever they could afford to get their hands on. Sterno, benzene, methyl alcohol, and other industrial chemicals were regularly added to illegal still production as preservatives and extenders. People were slowly and quicky poisoned by the hundreds of thousands.

Booze then…Weed now. Parallels

Just like has been the case with marijuana in the last 10-15 years, physicians during the 1920s were allowed to write prescriptions for medicinal alcohol. It is estimated that over 11 million alcohol prescriptions were written in the period. Then, as now, prescriptions for those that needed to self-medicate were easy to come by through both legitimate and illegitimate means.

Then, as now, shifting the selling of substances to the public from legal to illegal enriched the crime families in power. Rather than being a legitimate revenue source that the municipalities, counties, states, and the federal government could otherwise invest into treatment, education, and advocacy; it is (then and now) a giant funnel sucking vast amounts of currency out of our country into other countries and syndicates.

It is, and always has been, about the Benjamins

Then, as now, the moral imperative of prohibition both rewards and punishes the wrong people. Does that mean that legalizing all drugs, including those classified as Schedule 1 by the DEA will fix anything? Let’s examine that complicated question and this multi-faceted issue.

Booming Drug Trade in the 1800s

Many point to The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 as the defining moment in drug enforcement policy in the US. And it likely is one of them. However, many of us aren’t aware of the history leading up to that legislation. The League of Nations adopted several control measures prior to WWII in response to common use by the public of cocaine and opioids in consumer and medicinal products.

Opium had been a leading export of British and emerging American merchants throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. It is estimated that the British East India company cultivated and shipped tens of thousands of barrels per year around the turn of 1800. American tycoons like Warren Delano, Jr. (FDR’s grandfather) and Francis Blackwell Forbes got in on the act making millions sending opium in barrels to Chinese smugglers against the wishes and laws of the Chinese Emperors of the period. The two Opium Wars of the mid-1800s was a war between China and Britain to attempt to curb the exploding trade. Finally, a treaty in 1858 settled the matter between China, Britain, France—and indirectly the US.

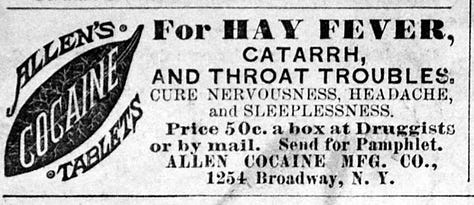

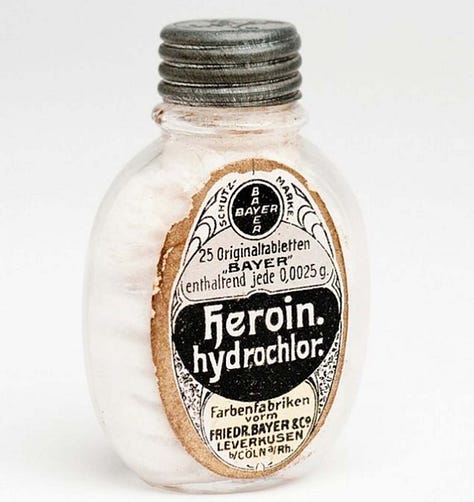

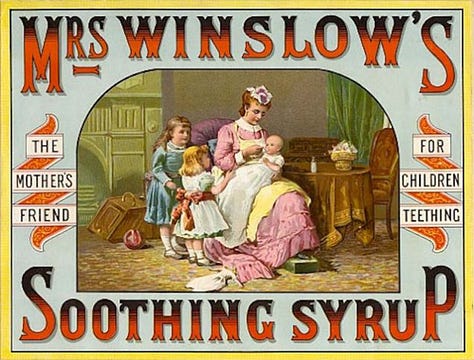

Well into the early 20th century, narcotics were used medicinally and recreationally across the World. Civil War soldiers were routinely given morphine which had been extracted as an isolate from opium in the early 1800s. Heroin was sold as cough syrup over the counter until nearly 1912, treating “nervousness,” menstrual cramps, headaches—even given to irritable or crying babies. The history of laudanum in the Western expansion is legend. Numerous consumer products contained cocaine until the 1920s. Famously Coca-Cola, ironically formulated by pharmacist John Pembert, had small amounts of cocaine. Eye drops, toothpaste, lozenges, even cigarettes contained cocaine.

Let’s talk about cocaine! Let’s shout about cocaine! But what about cocaine?

We think cocaine history began a few thousand years before the birth of Christ. Cocaine is derived from the coca plant, Erythroxylon coca—native to the Andean highlands of South America that run through Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile. The Andean people would chew these leaves to experience the high caused by their main ingredient, cocaine alkaloid. Chewing these leaves was incorporated into various facets of life, including physical work, religious ceremonies, and religious rituals. The coca leaf was a common aspect of the Inca Empire. Those busy little folks could build some temples—just sayin.

Then Spanish conquistadors arrived in South America in the 1500s. Hola! Que es eso? These foreigners enslaved the native people and forced them into brutal colonization. The Catholic Church, which of course funded the Spaniards worldwide conquests and fun, advised them to ban the use of coca leaves. “Yeah no.” The conquistadors realized they could work the locals twice as hard when they let them chew away. Eventually, the church fell in line with the idea and began collecting taxes on coca plants.

Cocaine didn’t travel well back then. The potency of the plants would degrade quickly due to conditions on ships and the length of time out of the sun. I think we know the real reason the leaves never made it back across the ocean. I mean, c’mon—you’re in the middle of the freaking ocean dealing with storms and sails and smelly mates and bad wine and mutinous chained oarsmen and such—and you got barrels of this stuff in the hold—and no one back home knows about it anyway—and.

It wasn’t until the mid-1800s that Europe found the wonderful substance. In 1859, Italian physician Paolo Mantegazza wrote the first essay claiming that coca had psychoactive properties and possible medical uses. For you ficitionistas, Mantegazza was also a prolific writer and publisher of fiction. In the same year, German chemist Albert Niemann isolated cocaine from coca leaves for the first time. In 1863, French chemist Ange-François Mariani introduced a coca wine to the public, contributing to the growth of recreational cocaine use in Europe. Weeeee!

In 1880, Wilhelm Lossen, no doubt sipping some of that spody-ody himself, created cocaine hydrochloride, which is the powder form of cocaine. This powder was used by many in Europe at the time. America discovered it around the same time. Austrian psychologist Sigmund Freud wrote a book titled “Uber Coca” in 1884 praising the effects of cocaine. And we kinda know the rest of the story.

First attempts at drug prohibition

In 1909, The International Opium Convention was convened in Shanghai, attended by 13 countries including the United States. This represented the first attempt at drug prohibition. What was evident then, as has been proven time and again in our numerous “wars on drugs” is that trade, commerce, and MONEY were the driving influences behind prohibition—rather than the welfare of the general population. This convention resulted in the global 1919 Treaty of Versailles, the primary objective being to introduce restrictions on exports. The treaty did not entail any prohibition or criminalization of the uses and cultivation of opium poppy, coca plants, or cannabis.

The second of these conventions was held in 1925 in Geneva, resulting in the creation of the Permanent Central Opium Board, managed at least in part by the League of Nations. I’m leaving out a lot of the gory details of all of this diplomacy and economic wrangling between nations in the early 1900s. But the evolution of this PCOB was to become the Single Convention on Drugs in 1961. This treaty has been modified a few times over the years, and as of 2022 has been ratified by 186 nations worldwide.

Classification and the beginning of the War on Drugs

The legislation that implemented the Single Convention on Drugs mentioned above was the Controlled Substances Act, passed into law under the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970. (how’d that work out for ya?)

The law created five schedules or classifications of substances with varying qualifications. The DEA and the FDA are the two agencies in charge of adding or removing various drugs into these “schedules.” Reeling it back a couple of paragraphs above, remember that the US really started outlawing drugs back in the early 1900s with The International Opium Convention and the Food and Drug Act of 1906 which created over 200 individual laws and statutes concerning public health and consumer protections. What the 1970 legislation, championed by Attorney General John Mitchell and signed by President Richard Nixon, did in effect was combine the dozens of laws that pertained to substances and also raised the level of federal law enforcement.

While many at the time thought that the Act actually made law around drugs more rational and sensible from the standpoint of classification, they also saw the law enforcement elements of it as archaic and over-reaching. One expensive study that emerged from the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) was the establishment of the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse. This study found that marijuana should be classified as a Schedule III substance rather than the harsher Schedule I classification. Chairman Raymond P. Shafer was quoted in the study as to their findings on weed. “The criminal law is too harsh a tool to apply to personal possession even in the effort to discourage use. It implies an overwhelming indictment of the behavior which we believe is not appropriate. The actual and potential harm of use of the drug is not great enough to justify intrusion by the criminal law into private behavior, a step which our society takes only with the greatest reluctance.”

Clear as mud

So, let’s examine just how clearly these laws, their jurisdictions, and the enforcement of such, were rolled out back then.

The first federal law to restrict the use and distribution of narcotics was the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914, which predated the Volstead Act and the 18th Amendment for alcohol prohibition by about six years. Both were indicative of the changing moral landscape in America.

In 1937 the Marijuana (spelled Marihuana in 1937) Tax Act was passed. What was clear about this tax was that it designed to destroy the hemp industry of the day. William Randolph Hearst felt that hemp threatened his timber and paper pulp dynasty. In cahoots with Hearst was Andrew Mellon, America’s wealthiest man at the time, Secretary of the Treasury, and a huge investor in DuPont who had a patented fabric alternative to hemp. Times change. Methods don’t.

The intent of the 1970 Controlled Substance Act was to establish conformity with the international treaty called The United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs.

The Uniform Controlled Substances Act, separate from the CSA, was created by the Justice Department to align with the federal legislation of the CSA. Because apparently, we needed more acronyms and bureaucracy.

There are three versions of the Uniform Controlled Substances Act on the books: the original in 1970, a 1990 revision, and another revision in 1994.

Every state in the union has the authority to adopt or ignore the Act. All but Vermont and New Hampshire have adopted one version or another of the UCSA.

States and their jurisdictions have the authority to adopt or resist any changes to the drug scheduling changes at the federal level. Most do adopt the changes but do have a hearing process to deny or resist.

Thus, the Uniform Act completes a top-down system of control in which drug policy originates through the international legislative process of treatymaking and United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs scheduling decisions and is automatically implemented through Controlled Substances Act provisions requiring federal scheduling of internationally controlled drugs, and Uniform Controlled Substances Act provisions requiring state scheduling of federally controlled drugs. Got it citizens?

Yeah, so now you know where all of this wonderful drug enforcement policy began. As our societies and cultures across the world have grown more sophisticated, and our federal and state authorities have claimed more and more regulation of human behavior as their own, we find ourselves in the current climate of vast differences between states in terms of how they regulate and enforce laws around drugs.

The War on Drugs

The war in its modern form began around the same time as the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. One of Nixon’s many proclamations was this one: “Drug abuse is public enemy number one.” Nearly 15% of all returning servicemen from Vietnam were coming home addicted to heroin. Many more were hopelessly addicted to high-potency weed exotics from Southeast Asia.

Despite his many well-publicized faults, Nixon’s efforts at the time have been lauded by many as primarily a public health initiative. History has shown that Nixon didn’t like blacks and he didn’t like hippies—the two biggest enemies to his White House. Still, historians who have reviewed his drug policies at the time, remember them more as a public health crusade. Under Nixon’s drug czar Robert DuPont, the administration actually repealed the existing 2–10-year minimum sentences for possession.

The DEA was created in 1973, replacing the existing Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. The name itself Drug Enforcement Agency, signaled a new stance. Nixon was of course disgraced, and Gerald Ford took the reigns as a quiet and resolute leader for his brief term.

It was really under the Presidency of Ronald Reagan that the country saw a vast expansion of federal attention to investigation and prosecution of drug-related crimes. The 1984 Comprehensive Crime Control Act, supported widely by politicians from both sides of the political aisle, was signed into law. The Act reintroduced federal mandatory sentencing minimums, increased the FBI budget ten-fold, authorized CIA involvement in international drug-trafficking, introduced the concept of civil forfeiture of assets by law enforcement, and began to gradually but immediately increase levels of incarceration nationwide. The much-discussed 1994 Violent Crime and Law Enforcement Act, championed by Texas House Representative Jack Brooks, and then Senator Joe Biden and signed into law by President Bill Clinton, continued to ramp up the level of incarcerations. The act had many provisions that increased incarceration and a vast federal budget increase to support the building of new prisons. As it related to drug enforcement specifically the most impactful was to make federal the mandatory sentencing of habitual offenders or “3-strikes rule” that many states had already adopted at the state and local level. The ‘94 bill made 3-strikes federal, and sentences grew in length.

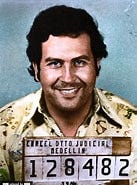

We’ve all seen the movie, read the books. Scarface, Cocaine Cowboys, and Traffic. The legends of Jon Roberts and Carlos Lehder and George Jung and Pablo Escobar and others have been widely portrayed in popular media. It’s clear from these accounts, whether true or scripted based upon truth, that the sides of right and wrong were never that clear. I’ve heard much of this corroborated by personal stories I’ve heard in the rooms of AA over the years from those that were there and escaped. Corruption, bribery, political influence, and all that dirty stinking money that needed to be washed and folded and put back into the accounts and bank vaults of the people with the right geography and properly influenced leadership.

It is estimated that in the 50 years we’ve been fighting this war, the US spends $50 billion per year, and has spent over a trillion cumulatively. I’d wager that number is egregiously under-estimated. Our money bought drugs. Our money fought drugs. Our money puts drug dealers and drug addicts in prison. Our money bribed politicians. Our money made people rich. Our money knocked despots from power. Our money influenced elections. Our money assassinated opponents. Our money traded arms for drugs—drugs for arms.

All’s fair in love and war. We Americans love our drugs. We, America, are at war with drugs.

So, given all of that very brief accounting of our institutional and cultural relationship with drugs—and my regular readers will remember that its always about the relationship to things that I’m interested in—where does that leave us in the modern world of short memories and decreased attention spans? Should we in fact legalize Schedule 1 drugs?

The Pharma Cartel

What would you call a pharmaceutical industry that has incestuous ties with FDA officials who make the decisions on an emerging drug’s narcotic classification, human testing, and approvals? What would you call the same industry with the deepest lobbying pockets in all of beltway politics, with hundreds of millions of dollars paid directly and indirectly to elected officials and unelected bureaucrats making regulatory decisions about their industry? What would you call an industry that routinely settles damaging health and class action lawsuits in the millions and billions of dollars? I would call that industry a drug cartel. There are few indications that this industry will do anything but grow in size and influence.

Current Decriminalization and Legalization of Marijuana

I lived in Colorado from 1990-2016, spending 10 years in Vail and 16 in Denver. Not only did I live in a historic downtown Denver neighborhood, but I founded and ran a company with dozens of employees with offices in the heart of what is called the “lower Platte valley” on the fringes of LoDo. Suffice it to say I had a front row seat for Colorado’s emergence as one of two states (Washington) to legalize the recreational use of Marijuana. The Amendment 64 passed in 2012 by just over 53% of Colorado voters.

“Dude it’s legal!” rang through the streets. The state of Colorado has historically always had a very strong tourism industry, averaging over $20 Billion in the state’s coffers each year. But after 2012 the mix of “tourists” changed dramatically. Friends and colleagues, users and non-users alike who had spent years in Colorado, noticed it immediately. Although Colorado had legalized medical marijuana licenses in 2000, and licenses were as about as hard to get as a sunburn, 2012-2015 was nonetheless a free-for-all. It was as if every male between 19-30 who had been living the last 5 years in a tent or in their parent’s basement moved to Colorado. A wee bit judgmental perhaps but that’s what it looked like, smelled like, and felt like. People rushing headlong to get in the weed business. Dispensaries opened on nearly every corner—more than Starbucks at one count in early 2014. The legion of armored cars that serviced downtown Denver tripled. Banks couldn’t and wouldn’t open accounts for dispensaries or wholesale growers, so the enormous amounts of cash had to go somewhere. Smash and grab robberies proliferated, thieves using cars and trucks as battering rams to knock down doors and windows of dispensaries and storage units to get to the cash stashes. Off-duty cops and private security jobs doubled their pay rates. The aroma of really good “kush” wafted throughout the downtown area. Denver has amazing weather most of the year—roll your window down type of weather—and just the act of commuting down 6th Ave or Speer Blvd became an opportunity for a contact high. One common occurrence was the regular DWS—Driving while stoned out of your gourd. The light would turn green in front of the mid-90’s Honda Passport a couple cars in front of you. You’d all sit there. Finally, someone would honk. You’d see a head come up, a blast of smoke come out of the driver’s side window, and the car would finally creep forward, allowing all of 3 or 4 cars through the light cycle. The average speed of cross-town traffic slowed noticeably. I’m not making this up—but in all fairness two things that may have exacerbated my own personal observations and irritation: I was driving a Porsche 911 purchased when I’d sold my company in 2009, and I was sober. The lesson for me was one of patience, and mine was tried every single fucking day.

In my business community, colleagues were taking communications and PR jobs in the cannabis industry left and right, as cash came flowing into the state from newly formed venture funds set up to capitalize on the bud rush. “We’re farm to table!” “Organic.” “No one knows gummies like we do!” “We have 30 more varieties than Heinz 57!” Startups sprung up like—well like weeds.

Effect on the Illegal Drug trade

One of the main promises of legalization was that it would eliminate or reduce the black market of illegal drugs and control the potency through regulation and licensing. Has that been proven out? The black market for weed has flourished in Colorado in the decade since Amendment 64 passed. In many cases, the illegal growers now have the legal industry as “cover” for their operations. California has had the same experience. Many illegal growers have found the licensing and regulatory process to be cumbersome and unprofitable at small scale. Many paranoid users and buyers, or those with criminal histories would rather not put their name and ID in the state database, required when purchasing marijuana legally. Using a database maintained by the Drug Enforcement Administration’s El Paso Intel Center, a recent report by the Colorado Department of Public Safety, found that seizures of marijuana coming from Colorado jumped significantly in the years following 2014, when Colorado’s first recreational cannabis shops opened. That settled in subsequent years, but in 2019/2020 state law enforcement had its largest pot bust in history involving over 250 homes and businesses involved in the illegal trade.

The flow of more potent drugs into the country

It appears to all who study it that the legalization of substances previously prohibited under law does not appear to stem the flow of more and more potent drugs into the US. The new scourge is obviously fentanyl. The chemicals are made in China, shipped to Mexico, assembled into pill and powder form by the cartels, and shipped across the border. This has changed the world for both casual drug users and addicts alike in that it creates fear, uncertainty, and a higher risk of death from the normal supply working its way down the food chain to the end user. The typically higher drug tolerances that normally might protect an addict of street heroin, meth, cocaine, or counterfeit pharmaceuticals; have no such defense against fentanyl. Addicts generally have a reliable dealer or supplier, but where does that supply originate? Casual users now have increased risk from buying the weekend gram or the 8-ball or the knock-off Xanex or Percocet or Oxy. Stories about first time users dying from fentanyl are many. Kids can buy pills on Snapchat and other social media sites with absolutely no idea where they come from or what’s in them. Would widespread legalization improve the odds by somewhat controlling the quality and integrity of the supply? Perhaps for some. But back to Colorado’s example, many users simply won’t ever walk into a retail store to buy their supply.

Eric Spitznagel wrote about “America the Stoned” in a July 18th piece on The Free Press.

The Sober Community

The talk in the rooms of AA changed. There have always been those that claim and practice what is called “California Sober,” which simply means that you’ve stopped drinking alcohol or using other harder drugs, but a little weed now and then was OK man—cuz it takes the edge off my anxiety dude—and it gets me through the day sober. Except you’re not. Sober. You’re dry and you might abstain from alcohol and other substances, but you’re most definitely not sober. For a person in recovery the definition of sober is simple. It means that you don’t indulge in mind-altering substances, and you’re working on your life program through the lens of this newfound clarity. You cannot do the work of recovery if you’re checking out of your life each evening. It’s called living an “examined life,” not a partially examined or weed examined life. Like I’ve said in many previous essays, to each their own. No judgment. Are those people better off without booze, coke, meth, heroin, or opioids in their lives? Sure they are. Are they practicing recovery? Most definitely they are not. What began to happen is that folks in the rooms began talking about this. “I wasn’t gonna say anything at all, but I’ve been smoking weed and taking a few gummies for the last year as I’ve been accepting chips for my sobriety milestones. It’s been all good until lately. The potency of the shit I’ve been smoking is so out of control it has really fucked me up. I’m wasted all the time. That’s not what I signed up for here. I’m done.” Another commonality in the “rooms” is the recovering alcoholic who is on several prescribed pharmaceuticals to treat the previously undiagnosed mental illness symptoms that only surfaced once they had achieved a level of abstinence from alcohol. No judgement here—sobriety and real recovery is hard and complicated. Only the individual knows if they’re actually doing the work.

The Money

At last count in 2022, Colorado had exceeded $10 billion in sales of cannabis and cannabis products. This has generated over $2 billion in revenue for the state from taxes and licensing fees. There are over 3,000 licensed businesses and over 45,000 licensed individuals working in the business. Marijuana tax revenue funds Colorado Department of Education programs such as the Building Excellent Schools Today (BEST) capital construction assistance fund and others. The dollars support community behavioral health programs including mental health services for juveniles and adults, crisis services, criminal justice diversion, the Circle Program, substance use disorder and detoxification services.

Much of the dust has settled down to a dull roar after a decade of tweaking regulation and enforcement. Recreational use of marijuana is legal in 23 states. 14 more allow medicinal usage. So in 38 states of 50 you can grow, possess and use weed in varying amounts for your own purposes. In most of those states, there are thresholds for what is considered possession with intent to distribute. That remains illegal. Even the legal growers have to jump through a lot of hoops to ship their products. It appears somewhat inevitable that there will eventually be a federal stance on legalization in order to combine law enforcement and revenue sharing. Again—the MONEY will be the reason.

Decriminalization of other Schedule 1 drugs

Colorado and several others states like Oregon have legalized psylocibin recently, and in the case of Oregon, their voter-approved 2021 Measure 110 legalized the personal use of other Schedule 1 substances like heroin, methamphetamine, PCP, LSD, and Oxycodone. The goal of Measure 110, passed in the wake of the George Floyd phenomenon nationwide, was to reverse racial disparities in policing, and was projected to reduce black arrests by 94%. The results have been mixed. The taxes from the sale of cannabis are awarded by the state as grants to programs that serve the community of users and addicts in the state. Oregon recently announced its first round of grants at over $300 million. Steve Allen, Oregon Health Authority’s Director, acknowledged that, nearly two years after Measure 110 passed, the availability of addiction treatment, including residential treatment beds and medication-assisted treatment for people with opioid use disorder, is “inconsistent” across Oregon’s counties. Measure 110 funding is largely not being used to address those gaps in addiction treatment and professional medical services. Under direction from the state Legislature, Measure 110 dollars aren’t being used to pay for treatment services that are also covered by commercial health insurance or the Oregon Health Plan.

But does any of this impact addiction or addiction treatment?

Will the money generated from the legal sale of drugs actually ever be applied to treating addiction? In theory, yes. In practice, it’s tricky. In Oregon’s groundbreaking example, a respected addiction expert recently spoke to the Oregon Legislature on the topic of Measure 110; “On the one hand we have highly rewarding drugs which are widely available, and on the other little or no pressure to stop using them,” Keith Humphreys, a psychology professor at Stanford University, told the state’s Senate Committee on the Judiciary and Ballot Measure 110 Implementation. “Under those conditions we should expect to see exactly what Oregon is experiencing: extensive drug use, extensive addiction and not much treatment seeking.”

Neither Humphreys nor another expert appearing before lawmakers — Oregon Health & Science University head of addiction medicine Dr. Todd Kurthuis, advocated for undoing Oregon’s pioneering law decriminalizing low-level drug possession, approved by voters in 2020 as Measure 110.

Many of these drugs carry a plethora of health benefits to many individuals. I’ve written about microdosing previously here. Marijuana in various levels of THC potencies has long been used and lauded for chronic pain relief, late-stage cancer patients, relief for those suffering from anxiety, and others. Most studies done in the last decade point to direct links between legalization and increased usage. In the state of Colorado’s own study, usage was shown to have increased 24%. Concerns have arisen around access of young people and the effects of increased usage on developing brains. Increased usage of weed appears to also increase drinking behaviors among regular, young adult users.

Harm Reduction Efforts

Many communities, municipalities, and states have adopted a harm reduction stance towards chronic users. Realizing that it’s likely better than wasting resources prosecuting and incarcerating these individuals, they instead try to help them not make things worse.

From the SAMSHA website: “Harm reduction is a practical and transformative approach that incorporates community-driven public health strategies — including prevention, risk reduction, and health promotion — to empower people who use drugs (and their families) with the choice to live healthy, self-directed, and purpose-filled lives. Harm reduction centers the lived and living experience of people who use drugs, especially those in underserved communities, in these strategies and the practices that flow from them. Harm reduction emphasizes engaging directly with people who use drugs to prevent overdose and infectious disease transmission; improve physical, mental, and social wellbeing; and offer low barrier options for accessing health care services, including substance use and mental health disorder treatment.”

OK so there’s a lot of empathy and compassion in those words and in the policy. I’m good with that. You have to meet people where they are to begin to guide them to a better life. For these individuals that better life must be clean and sober. Half-measures avail us nothing. Harm reduction strikes me as a bit of a half measure, but I’ll stay patient and open. The only way that you can empower people who abuse drugs is to get them clean and sober. So, if the intent is to lower the barrier to treatment, then harm reduction is going to help. If the intent is to create safe spaces to use and deal drugs in public, then not so much. The evidence is out there that these policies can be effective in keeping addicts safe from transmittable diseases, reduce overdoses, and eventually guide someone to treatment. Again—if you can provide access to treatment and counseling with the end goal of helping the individual get and stay clean—you’re helping. If you’re only enabling them to perpetuate their behavior but in a new, supposed healthier, taxpayer-funded space—then you’re not helping.

There are counties in the US that have asked their law enforcement officers to stop carrying Narcan. Why? Because they’re tired of reviving the same drug addicts over and over again just to see them overdose over and over again. Their attitude is that’s it not in their hands to save that person’s life when that person obviously doesn’t care about their own life. I don’t disagree with the frustrated sentiment, but I do disagree with the policy. I know personally several individuals who have lived long, incredibly productive lives after having nearly died a dozen times during their using days.

What about the Addiction Treatment Industry

There’s not enough of it. What is out there isn’t available to everyone. There’s also a lot of scammers and nefarious operators. I’m very closely involved as a volunteer and a donor with one of the leading addiction treatment organizations in the world. Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation is a result of the 2014 merger of two icons in the field of addiction: The Betty Ford Center and the Hazelden Foundation. They now operate recovery centers in 20 states, treat thousands of patients annually, have an annual budget from operations and charitable giving in the hundreds of millions. The professionals in the organization are among the best in the industry and have saved countless lives. They saved mine.

Even they are having a hard time making a go of it. Here’s a watershed moment in national politics and health care policy that impacted every single treatment organization in the industry. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is known colloquially as Obamacare due to it being passed into law in March 2010 under his administration. Many of the provisions didn’t take effect until several years later as it was implemented in phases based upon participation by the public. One of the key tenets of ACA was around substance use disorder and addiction treatment. A person could not be denied care based on a “pre-existing condition” meaning in this discussion, prior treatment for addiction. Additionally, every insurer had a requirement to cover treatment for addiction and mental health services. It opened up access to treatment for many more individuals seeking this type of treatment. ACA was, and still is, viewed as a very positive step towards treating more people in need.

What it also did was significantly alter the business side of the equation for providers. Hazelden Betty Ford was no exception. Both organizations pre-merger, particularly Betty Ford, had a reputation as a place where the rich and famous went to hide out and get well. The reputation was well-earned and the long list of high-profile actors, musicians, business icons, and athletes that recovered in the Coachella Valley is legend. The Center could set its own pricing. Patients paid their bills in full, with no help from insurance. The staff was top notch and well compensated for their professional and compassionate work. The treatment industry for many years worked under a multi-tiered system. There were public options, private options, hospital based, Mom and Pop based, and military based. You received treatment based on what you could afford. They all had plenty of customers, and they all found a way to thrive.

ACA changed all of that. For “self-pay” treatment organizations like HBF is turn a retail business into a wholesale business. Whereas historically self-pay patients accounted for 90% of their customers, with the remaining 10% comprised of scholarships paid by donors, and some insured patients. After ACA, their business model shifted to nearly 90% of their patients presenting insurance coverage, with the remaining 10% paying for their own care out of their pocket. Because of course, even if you could afford to pay for care yourself, who wouldn’t rather have their insurance provider pay for it? Keeping the “record” of addiction treatment care off of your permanent healthcare record was always a powerful motivator for many high-profile people, but it turns out money is a greater motivator.

For those organizations that were historically surviving on payments from insurance providers, the season turned as well. Adjusters—health care specialists as they’re affectionately known in the industry—were now in charge of determining where a person could go for treatment, for how long, and what type of care they could receive. It changed the way that addiction treatment clinicians could make recommendations for in-patient residential care vs. outpatient care, what they recommended in terms of after care, sober living, etc. It all was determined by the insurance adjusters. “Patient XYZ has coverage for 17 days of drug-assisted outpatient care. Period.”

From the side of the insurers there’s no doubt that oversight is necessary. The abuses have been legend. We’ve all seen the documentaries and Netflix shows about the patients trading benefit cards like dime bags, nefarious and corrupt treatment centers and sober living facilities charging millions for care that was never provided to ghost patients. Florida seemed to be ground zero for addiction treatment abuses as soon as the Affordable Care Act was passed, and dozens of executives are serving time for criminal fraud and other crimes. There are few, if any, industry standards that run across industry providers. “Rehab” ain’t what it used to be. Interventionists working with families, referring physicians, law enforcement and courts all have to be able to develop relationships with trusted treatment providers. They need to know they can send an urgent patient there in a timely manner.

The greater point of all of this is that the demand for high-quality, compassionate treatment is greater than ever. Simultaneously, it’s harder than ever to run a quality treatment organization profitably, attract caring and qualified clinical staff, and most importantly—be able to afford to provide adequate and necessary treatment to their patients. Many organizations have had to cut back or eliminate vital supplemental programs that are vital to long-term recovery, such as programs for the family and the children and the employers.

Insurance adjusters have become the frontline decision-makers in determining whether or not an alcoholic or addict in need gets the care they need.

There isn’t a lot of good cheer in the sentence above. I’m not sure who has more power over legislators—pharma or insurance, but they’re neck and neck contenders.

Summary Findings

This entire essay has taught me a few things. I thought I had an understanding of the history of the drug trade and of prohibition. I was missing a lot. I now have more questions than answers. For example;

—Why are we wasting our breath asking the Chinese to stop poisoning our citizens with Fentanyl? They are nothing if not long-game thinkers and historically aware. The US and Britain poisoned much of their population with imported opium for hundreds of years—and got rich doing it.

—Why do we continue to pour billions into fighting the cartels in Mexico when we don’t even have the political will to change or enforce our own archaic immigration system?

—can we as a country continue to spend vast amounts of money and resources to fight to stop an ever-growing tide of drugs, both legal and illegal, that is demanded by its public?

—Why do we continue to allow the pharmaceutical industry to remain so powerful, untouchable, and corrupt?

—Why do we allow insurance company employees to make decisions about care?

—what do we accomplish by differentiating between illegal and legal, when the recent (and still ongoing) opioid crisis proved that legal and prescribed drugs are just as addictive and dangerous as illegally-obtained street drugs?

—we know prohibition doesn’t work. Why do we continue to enrich cartels, rather than putting the dollars of American drug users into developing more treatment options that are less dependent upon insurance coverage?

—shouldn’t we be focusing on the demand? On ourselves? Is that even possible? Are we as humans simply incapable of going through life unmedicated?

Here’s what I do know

I know that all of this can seem hopeless at times. Hopeless does not work for me. Without hope in our lives, we might as well just pull the chute now. I also know that recovery works. I’m a living, breathing example, and I know thousands of others by name. We cannot stop trying to help people recover from the hopeless grip of substances and from the wreckage caused by dangerous addictive behaviors. I know that people in the grips of addiction or substance use disorder do not give a rat’s ass about legal vs. illegal. They will get what they need when they need it.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) released the results of its annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) back in 2021. They’re working on the current one as we speak. Some pullout stats:

—65 million people aged 12 or older used illicit (their word) drugs last year. 22% of the population. You know its higher than that, because—well—it’s a survey.

—46 million people aged 12 or older (or 16.5% of the population) met the applicable DSM-5 criteria for having a substance use disorder in the past year, including 29.5 million people who were classified as having an alcohol use disorder, and 24 million people who were classified as having a drug use disorder.

—94% of people aged 12 or older with a substance use disorder did not receive any treatment. Nearly all people with a substance use disorder who did not get treatment at a specialty facility did not think they needed treatment. NINETY-FOUR FUCKING PERCENT.

—1 in 5 adolescents had a major depressive episode in the last year. 75% of those had symptoms that were considered severe impairment.

—12.3 million adults aged 18 or older had serious thoughts of suicide in the past year, 3.5 million made suicide plans, and 1.7 million attempted suicide.

That’s all the bad news. Here’s some good news. Of the (few) people who admitted to a substance use disorder and sought treatment, the numbers are:

—7 in 10 (72.2 percent or 20.9 million) adults who ever had an admitted substance use problem and had sought help considered themselves to be recovering or in recovery.

—2 in 3 (66.5 percent or 38.8 million) adults who ever had a mental health issue considered themselves to be recovering or in recovery.

I don’t even know really how to end this essay. It was a big, meaty one to tackle. It grew in size and scope the minute I started writing it. What I started with the simple idea that legality/illegality matters not to an individual who is intent on satisfying their itch. The rest of it grew from there. I hope you learned something. I hope you enjoyed it. I promise lighter fare next week.

This was such a great essay!

It is so in-depth and well-reasoned.

And I totally agree with your overall point, about the law not stopping any addicts.

I think you said it beautifully at the top of the essay when you said — “The Law does not enter into the mind of an addict. It isn’t the last thing on their mind—it isn’t even there.” — I was an addict for more than 10 years and I couldn’t agree more with this summary.

Thank you Hilda your words mean a lot to me.