Is that you Dad?

My smell memory is older than my actual conscious memory. The earliest recollections I have of my Dad aren’t visual. They’re from before that. They were in my nose. I smelled sneakers, socks, and leather basketballs. And sweat, and varnish on old wood floors long before I remember seeing those things. Archie was a hoopster. A damn good one. A shade over 6’2” and about 180 in his playing days—quicker than most around him. Deadly accurate shooter. I was born a week after his last game as a collegiate All-American for the San Diego State Aztecs. I don’t remember in my mind actually being in those gyms with him. But I know I was. I can smell it.

We develop the sense of smell in the womb. It is the first fully developed of the senses.

Experts will tell you that scent, emotion, and memory are deeply intertwined. The smelling takes place in the olfactory bulb which sits right up front in the brain and sends signals directly to the body’s limbic system—including the amygdala and the hippocampus. These regions very directly relate to emotion and memory.

Businesses of all types have attempted to capitalize on the sense of smell. We can all be triggered in one way or another by an evocative scent from our past. Or a new one in our present. For decades marketers across many product verticals have examined, tested, and injected scent into their offerings. Perhaps you’ve had the experience of a past lover who wore a particular scent, and the long-lingering memory of that renders us unable to imagine that scent on anyone else.

There are even olfactory marketing agencies advising big brands on the topic. According to pediatricians and scientists, the sense of smell is the only sense that is fully baked (mmm—baking) while still in the womb. and it’s not until age 9 or 10 that sight takes over as the most developed sensory perception. Scent can move us. It can drive us wild. It can alarm us or turn us away. I remember vividly a scene from the 1996 film “Michael” directed by Nora Ephron, and starring John Travolta, Andie McDowell, and William Hurt. Great scene in a country bar where Andie McDowell first realizes that the basis of her fascination with the chain smoking and unkempt “angel” Michael is that he smells like cookies.

One more point about our sense of smell that is timely. Many people who were infected with SARS COV 2 during the last few years lost their sense of smell (and taste). One of the reasons why this particular symptom was so utterly disorienting was all about its direct impact on emotions and memory.

Back to dad. He and my mother welcomed me into the World as their firstborn while they were still finishing college. Mom had set aside her full academic ride at USC to join dad in San Diego while he was finishing up his degree and college basketball career. They were 22 years old. The scents I associated with my father changed as I aged. After shave, hair gel, the smell of a men’s suit. But these were as I grew up and each was directly associated with a sight memory of those things.

Other visceral and important, yet perhaps unconscious smells from early in my life. The sea. New asphalt. Rubber cement. My Grandpa Virgil’s cigarette breath. Citrus in the air. Of course, the smell of Mom. Grandma’s rhubarb pie. Sweaty forearms. (I know—weird one—but I’m sure you’ve got a couple too.)

The word “pheromone” is now commonly used, but is a word only created in 1959 a year after I was born. It describes a chemical that is secreted by other living beings from the outside world but can affect us internally as a hormone would. Behavior is affected. Emotions are heightened. A physical reaction may occur. Flowers, trees, pets, other humans—attraction or repulsion based on scent. I’m actually allergic to dog dander, but my life consists of four, seventy-pound beasties in my house and on my furniture. I relish sticking my face in their neck fur and smelling the essence of them. I’ve dated women that I matched up well with, and adored, and yet—I just couldn’t. They just didn’t smell right.

This is fun to explore

As I was writing this essay, I queried friends and other writers on Substack about this concept of early scent memory. A waterfall of responses sharing honeysuckle, mom’s pot roast, the smell of queso. One writer, whose father owned a tackle shop and boat ramp, remembers the smell of gas vapors, fish, and hydrangea. Others called out mud, cut grass, blood, coffee, street pretzels, cigarettes, a dad’s pipe. One said his youth smelled like Margaritaville. That’s a household worth writing about. Scent predates language. Scent predates sight. We cannot recognize or assign meaning to scents we smell as babies and small children. But the memory is already deeply seated.

Mom and Dad

Our parents affect us on every level. “Thank you Captain Obvious!” Life is lived by human beings in a cascading series of extending, denying, learning from, letting go of, and hopefully accepting the lives and gifts of our parents. Even those who have lost their parents, don’t know them, or have had multiple sets of parents, carry these conscious and unconscious markers and influences. Metric tons of material have been written about the particular relationship between fathers and sons—and first sons. I could sense my father before I saw him. Energy is a powerful thing, and my dad was a powerful man. Born in 1935 into poverty right smack in the middle of the depression. Poverty back then wasn’t what it is today. Back then it was ubiquitous. It was life. But as dad and mom have told those stories to us in later years, they didn’t know they were poor. Everyone was. What they remember is the love and the comfort and the adventure. Their parents were doing the absolute best they could. Which is what all parents do—regardless of the outcome. They invest time, money, training, love, tradition, and belief systems into their offspring. They hope and they pray—oh do they hope and pray.

Father’s Day is about honoring Dad

Arch is a living American success story. He represents exactly what the dream of America was and still is. Coming from nothing doesn’t mean you must remain nothing. He dribbled and studied and worked his way through community college and then university. His career accomplishments have been studied in MBA programs. Dad may have often fancied other paths or wanted to explore his “truth” and his “authentic self.” But these are fanciful luxuries of our current time. In his generation if you had a young family and wanted more for them than what you grew up with, you put your head down and you went to work. If you did, the possibility—the dream of success was achievable. Not to all—but to some. Those that had the skill and determination, seized on a fortunate opportunity, and never looked back. Like my dad. His single-minded sense of purpose and his work ethic have always been remarkable. To that generation from which my dad comes, there was no greater crime than wasting time, opportunity, or talent.

All of this likely fed his ongoing confusion with his oldest son. I had periods of focus and attention. I excelled at things that interested me. I am an Aquarius BTW—so there’s that. The world was fascinating to me, and I had no idea yet what to do with it. I was raised in a disciplined household. I did the things expected of me—went to church, had good manners, kept my elbows off the table, respected my teachers and elders. I had measurable success in sports and performing and Boy Scouts. But every once in a short while, I’d just go off and do something—because it looked fun or interesting, and I was curious about it. Often it was against the rules. I did it anyway.

I remember sitting down with him to talk about a decision I’d made. I was seventeen years old—in the fall of my senior year in high school. I would turn eighteen in February. We had just finished a successful football season. I had been named 2nd team All-conference for my play as QB and free safety. My next stop was basketball. For a decade or more I’d been playing sports seasonally. As the fall leaf piles began to cover with snow flurries, football season would turn to basketball season. When the trees first burst forth with their buds, it was track season. Summer meant Boy Scouts, baseball, girls, cars, and jobs. There was a pace—a familiarity to it for a long time. My two younger brothers played their part in the dance by choosing their sporting pursuits in kind.

In that looming conversation with my father, I intended to break that rhythm.

Our basketball (the Clayton Greyhounds) team was legendary in the region. We’d finished with a record of 29-3 my junior year and lost the Missouri State 3A championship game by a point. Brief foreshadowing: The morning after the big game my dad scraped me off the front yard where I had passed out before making it inside. I was wearing my letter jacket and still clutching a half-gallon milk jug of warm Bacardi 151 and coke. I was the team’s defensive specialist—a 6th man off the bench—sent in to press or shut down the quickest or highest scoring opponent. Although we would be losing a couple of key starters, expectations soared for a successful senior campaign. I would likely be the offside guard on the starting five next season. My head coach was also the Dean of Students. Dawson Pike was a stoic and powerful leader of young men. When he spoke, you listened. I went to his office one day in late November and announced that I wouldn’t be playing basketball this coming season. Instead, I told Coach Pike that I wanted to play the role of “Curly” in our school’s winter production of “Oklahoma.” I just came out and said it. And waited. Perhaps I expected something different from him. I don’t know. His response was “good for you Dee.” He asked about the show, asked how I’d arrived at that decision, did I have to try out? How do you want to tell your teammates?

Dr. Charles Prokaski, another remarkable leader of young people and Director of Music at our high school, had come to me after one of our choral sessions, and told me he’d always wanted to put on “Oklahoma” at the school. To this day, I certainly hope that other high school students get the opportunity to take part in the type of ambition and vision that Dr. “Pro” had for us. He told me that he needed a Curly. He told me that he was obviously proud of our Greyhound basketball team and knew the wide swath I’d cut through our high school sports. His direct challenge was: “you have the talent to do both, but not the ability. We will rehearse when you would be playing or practicing. You must choose.” He asked me to consider it. I didn’t have to. “Sounds like fun. I’m in.”

Animals have an inherent ability to smell fear. Some humans claim to be able to. Who knows? If fear has a smell, then I reeked of it before I sat down to tell my dad of my decision. All I remember now about the conversation is some silence. But truly—there was nothing but loving support. Maybe an eye roll or two but I don’t recall that. At the age of seventeen, the anticipation of having that conversation with my dad was exponentially more difficult than the chat itself. Basketball had been his game. How could I make him understand my decision? What possible future could there be in singing my way around a high school stage?

But isn’t that how it works?

The anticipation of a thing can make us drool, melt, shrink, swell, and make the heart race. One part of alcoholic thinking is that there is no stopping power between the anticipation and the action. Even if the actual doing of the thing works out, which it sometimes does, we have no braking mechanism between the desire of anticipation (amygdala—lizard brain) and the rational decision whether to do the thing or not (frontal cortex—reason). Even for “normies” the reason why anxiety, worry, fear, longing—can all be so incredibly powerful is the function or dysfunction of that braking mechanism. It’s very difficult to shut down those quick-rising emotions. Or to allow yourself to feel those inevitable feelings, and then be able to de-escalate with some form of mindfulness. Evidence the pharma culture we live in.

If you’d like to imagine what a drug addict or alcoholic feels when they reach for a bottle or a pill or a needle, think back to when fear or anxiety or worry rose up to an uncontrollable pitch inside you. What do you do? We reach for the relief we know because we know it works. In sobriety we have to find healthier ways to respond. It is really fucking hard work.

Dad and I survived that conversation. We survived dozens more seemingly confusing choices I made over the decades. I know deep down in my fibers that my parents wanted nothing but happiness for me. They’d both provided safety, comfort, and opportunity. What they also gave me—and this has likely always been the confusing part for them—was a chance to be fearless. They had necessarily grown up a world where planning, effort, and control led to expectable outcomes. My strategy (or lack thereof) was to run towards things that looked fun and interesting, regardless of the outcome. If it smelled interesting, I went for it. I definitely was still motivated to please them and win their approval most times—but not always. I took big swings towards fun—towards uncertainty. For that freedom, and for many other things, I am grateful beyond measure. Without the net my dad provided, many of the experiences I outline in these essays would never have been possible. I was gifted with the options to fall flat on my face as often as I wanted to or needed to. I’ve heard my dad say to me many times over the decades, “son, I know you might hear what I’m telling you, but you are going to do what you’re gonna do anyway.” And I did.

Disclaimer: I’ve not had the blessing of being a father.

I’ve had plenty of opportunities to be one and for a long while I wanted to be one—until I didn’t. Life, dysfunctional relationships, and my addiction got in the way. I’ve channeled my parental love instincts into rescuing and caring for dogs, and in trying to be a good uncle to my four amazing nieces. Dog parenting isn’t close to the same thing as parenting human children—not even close. Certainly, dogs teach you about the concept of unconditional love. They also teach you in a very painful way about grief given their relatively short lives. But dogs don’t wreck cars, they don’t have to be bailed out of jail, they don’t keep you up nights on end with worry, they don’t get you called into depositions, and they don’t often willfully act out against your counsel. I did all of those things to my parents.

I think if you asked my dad what he’d change about me the list might be long. He might remember how often I disappointed him, embarrassed him, and put him in an untenable position—even at the expense of his own solid reputation. I’ve never asked him—t’s likely irrelevant at this point. He and I have made peace now and we’re OK. If you asked me the same pointless question about him, I’d say just one singular thing. That he’d verbally validated me more. Maybe have said “I’m proud of you” or “I love you” more often. He knows this because I’ve told him. His response, so perfect for the man he is, is that he shouldn’t have to tell me—I should know by his actions. And I do. I know that my parents love me unconditionally. That goes without saying. They’ve proven that by their actions time and again. But I would have liked to have heard the words from my dad more often. As I’ve said, we’re OK now.

Arch turns 88 a couple of weeks after Father’s Day. I’ll soon get to be with him for a long visit. The gratitude I feel to still be able to talk and laugh with him, share meals, play some golf, watch some sports on television together is immeasurable. Especially when so many of my friends and peers don’t have that same opportunity.

One of those actions my father took to demonstrate his love for me is the one that saved my life. The intervention on Thanksgiving 2009. My real commitment to sobriety only began after my dad stepped in and made the same commitment. He is quite literally the only person on the planet that could have. Others had tried. My fun-loving friends certainly weren’t going to interrupt me. I had a boss, a business partner, several girlfriends all try. There were two failed attempts at getting clean and sober in my 20s, I tried again in my 40s, and finally it stuck in 2009. In those prior attempts, my discussions with my dad revolved around him telling me about responsibility, self-discipline, my decisions, my health—the usual. In other words, he didn’t understand alcoholism any less or more than I did. “It’s not my problem to solve Dee—it’s yours and yours alone.”

He would watch from a distance as I would achieve moderate success in one work pursuit, get bored, and drop it like a bad habit and move on to something else. He would help me financially if I needed it while I chased successive dreams of building this business venture or that relationship. All the while I’m sure he felt the same thing I felt deep down—what could I potentially be or achieve, if only. On paper I was succeeding. On the face of things, I was showing up. But something just didn't smell right much of the time.

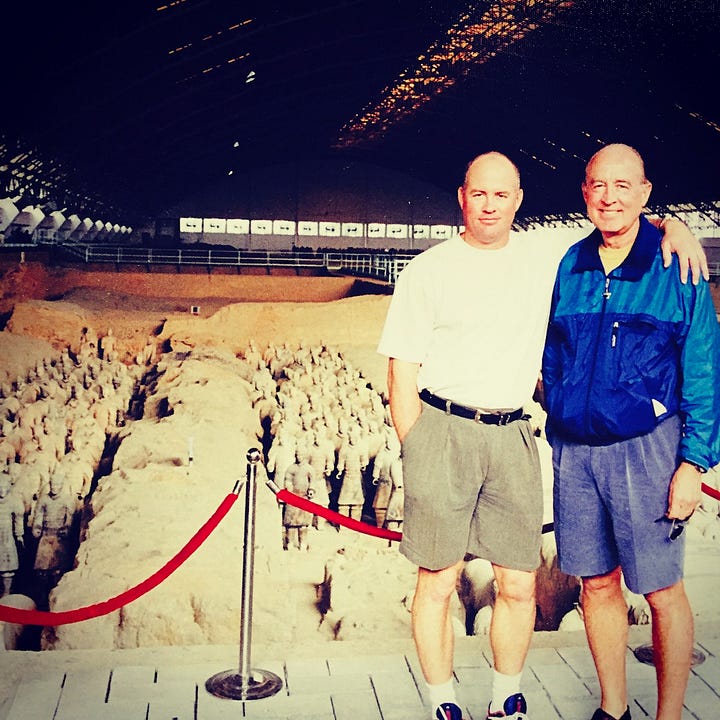

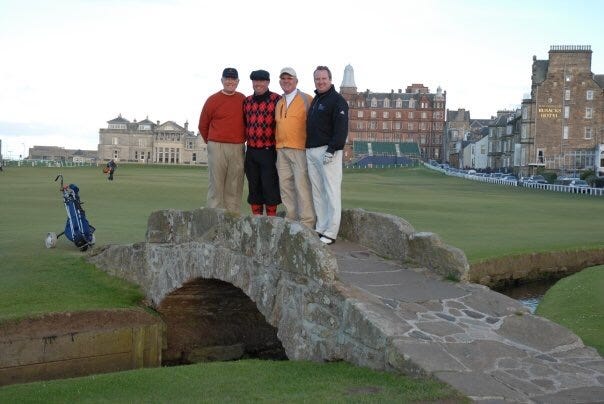

We did all the wonderful things families do together. I did my best to be a loving son, brother, uncle, nephew, and grandson. My father and I were blessed to take some incredible trips together as father and son. Inside China for 29 days. Golf trips to Scotland and a dozen US destinations. We invested in business opportunities together. That’s the insidious and baffling part of alcohol. You can pull it off for a while—sometimes a long while. Everyone drinks, right? So what if I just happen to be better at it than everyone else around me? One of the really brutal tolls of alcoholism (among many others) is that in those rare moments of sanity and clear-headedness, the person suffering knows they can do better. Carry that backpack around for a bit and feel the weight of it.

I could smell something coming…

I knew something was coming that fall of 2009. Some people call it intuition, or spidey-sense. I could smell it. But just like those early memories instilled in us that we don’t recognize until much later. My business partner and I had sold our company. I think Dad was proud. What I know for sure is that he felt alarmed. I was flush with cash and on a bad trajectory. The only thing I was smelling in the fall of 2009 was the sickly-sweet Johnny Walker Black leaking from my pores on any given day. I’ve talked about the decisive father/son golf weekend in a previous essay here: Tee it high and let it fly - by Dee Rambeau (substack.com)

Whatever other thoughts he had in those couple of months between September and Thanksgiving, he must have also felt that he simply had to try. And I’m sure he was exhausted by my mother’s worrying. With the experienced counsel of his best friend Rob, a longtime recovering alcoholic himself, Arch likely came to the conclusion that although none of this was his fault, he might just be the missing tool necessary to fix it. He had to try.

I cannot say that my decisions or opinions have aligned with my dad’s any more often in the years I’ve been in recovery. He has been presented with evidence of the disparities in our thinking many times. What I can say is that there’s more acceptance. We have had the opportunity that many families of alcoholics don’t ever get—a chance to come together and heal.

“Thank you” sounds trite and obvious. I’ll say it anyway. Thanks Dad. I love you. Happy Father’s Day. You’ve always been the rock that I could crash against.

Recovery and personal growth has created new access to memories that I’d blocked or drown out for a long time. Just like the early scent memories of my youth, whether sweaty socks and leather basketballs, or rhubarb pie, or the sun-dried dirt of a newly-created subdivision, the iceplant that grew wild down the ravine behind our house, or the pungent rubber-on-asphalt smell from the skid marks of my new bike—right now everything smells right. It smells like love.

What a beautiful integration of personal narrative and science, with scents meandering through in the most inevitable and healing way, like a river. Happy Father’s Day to your dad.

A beautiful tribute to yourself and your Dad.