Hello readers! Welcome to our newcomers. I’m grateful for all of you who take the time out of your busy schedules to read my essays. I’m publishing on a Thursday today, as Friday is stacking up as a whopper.

This rumination came out of the blue—a conversation that triggered an important memory—and a seed for an essay. I hope you enjoy this dip into the concept of split personality as it relates to addictive behavior. I’m certainly no scientist or psychiatrist—I can only relate and write about my own experience, strength, and hope.

Please enjoy. Hit that Like button and send me your comments if you’re compelled.

I’ve often talked about how my core personality is relatively unchanged since I quit drinking and using nearly 15 years ago. What has changed is which aspects of my personality come to the forefront. Each of us has light and shadow inside of us. Each of us struggles with fears and insecurities. Each of us is capable of truth and lies.

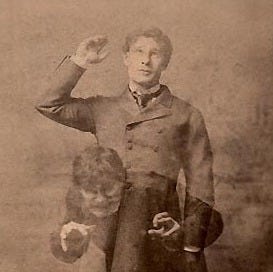

I’ve talked with many hundreds—perhaps thousands—of people in recovery. In those conversations—and also in many circle-of-chairs meetings—a consistent theme has arisen. The catch phrase is Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. In other words, the idea of having a good and an evil persona with each of us. Alcohol or drugs can, in my experience, be the trigger that reveals the less attractive and more dangerous of the two.

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was an 1886 novella written by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. There are multiple imaginative versions of how Stevenson wrote Jekyll and Hyde—that it came to him in a dream—that he burned the first manuscript after being appalled by it—that he wrote it during a 3-day cocaine binge. Whatever the case, the concept of Jekyll and Hyde has long existed in the zeitgeist since Stevenson’s telling.

The transformation from the renowned physician Dr. Jekyll to the deranged and murderous Mr. Hyde was caused by a serum concocted in his lab. In AA-speak that serum could clearly be alcohol. A normal, upstanding citizen of the world becomes a different person while inebriated. Are they a different person? Or are they just revealing a dark side of their personality that in a sober state is locked down within a moral code and societal rules?

Many scholarly interpretations of what Stevenson’s book represents, including:

—Freudian discussions of duality as it relates to the Id, Ego, and SuperEgo.

—A discussion of Scottish vs. English nationalism.

—Another take bringing the class division of the time in London into play.

—A religious take on good and evil—which Vladimir Nabokov dissents—saying that by Victorian standards of the time Dr. Jekyll is not a good person to begin with.

One compelling—and more modern take—is that addiction or substance abuse is a central theme in the novella. Stevenson's depiction of Mr. Hyde is reminiscent of descriptions of substance abuse in the nineteenth century. Author Daniel L. Wright, in his 1994 book The Prisonhouse of my Disposition describes Dr Jekyll as not so much a man of conflicted personality as a man suffering from the ravages of addiction.

In chapter two of the Big Book of AA, the Jekyll and Hyde syndrome is laid out as follows:

Here is this fellow that has been puzzling you, especially in his lack of control. He does absurd, incredible, tragic things while drinking. He is a real Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. He is seldom mildly intoxicated. He is always more or less insanely drunk. His disposition while drinking resembles his normal nature but little. He may be one of the finest fellows in the World. Yet, let him drink for a day, and he frequently becomes disgustingly, even dangerously, anti-social. He has a positive genius for getting tight at exactly the wrong moment, particularly when some important decision must be made or engagement kept. He is often perfectly sensible and well-balanced concerning everything except liquor, but in that respect he is incredibly dishonest and selfish. He often possesses special abilities, skills, and aptitudes, and has a promising career ahead of him. He uses his gifts to build up a bright outlook for his family and himself, and then pulls the structure down on his head by a senseless series of sprees.

This is by no means a comprehensive picture of a true alcoholic, as our behavior patterns vary. But this description should identify him roughly.

In my own history I had a Mr. Hyde. He was named Larry. Larry could be alternatingly funny—albeit often way over the line of appropriateness—and warm and cold and distant and occasionally a complete asshole. Larry forgot what he’d said and done the night before. Larry drove drunk. Larry lied to people when the truth would have been just fine. Larry didn’t show up. Larry was expensive.

My Larry was coined by a good old friend of mine in the ‘90s when I lived in Vail. One of the most well-known characters of Vail, Steve Sheridan, nicknamed The General, was a ski shop owner—ski tuner to the stars of World Cup—and a friend to all. A legendary local who is still thriving in that tightknit community of Vail. We’d often tip long-neck Budweisers together along with the occasional shorties of Jägermeister. One night, in the middle of one of my drunken diatribes to whomever was within earshot, General said laughingly, Yeah sure…OK Larry. And it stuck.

After I moved away to Denver in the early ‘oughts we stayed in touch, and I’d often reconnoiter with General on quick trips to Vail. Having started my entrepreneurial phase as a software mogul—in my own grandiose mind—I had deservingly graduated to Johnny Walker Black, and Larry was popping in on a more regular basis.

The nickname Larry was kept pretty close to the vest among my friends over the ensuing years. When I finally got clean and sober beginning on November 23, 2009, my counselor and my small group members at Betty Ford encouraged me to resurface the idea of Larry as a persona that I could say goodbye to—as if he were someone who had perished—allowing me to grieve Larry. I wrote several letters to Larry—the details aren’t important here for our purposes—but suffice it to say I processed a lot of anger, regret, and shame while addressing Larry. Finally—in my last letter—I felt that I had vanquished the shithead to the graveyard.

After returning home to Denver and becoming fully engaged in my daily 7 AM York Street meeting, I asked a small group of closed-mouth friends to join me for a funeral. For the ceremony I had to find a quart bottle of Johnnie Walker Black. The empties that had previously littered my home and trash bin had been effectively disposed of by my friends while I’d been at Betty Ford. I walked fearlessly into a neighborhood liquor store and purchased one. I was dutifully accompanied by a friend. We held a somber afternoon funeral ceremony in my back yard.

I dug a small grave as the attendees and my two dogs Bogart and Pistol Pete looked on. Once the hole was dug, I poured the contents of the scotch into the hole. I placed the empty bottle, the letter, and my favorite crystal monogramed drinking glass in the hole. After filling in the hole and smoothing the dirt, I dropped my six-month AA chip into the soil as a headstone. I read one of my Larry goodbye letters. My attending friends had a few choice comments for Larry as well:

Fuck off pal—you’re not welcome here anymore.

Hit the bricks you drunken lout.

I don’t think we buried you deep enough. I’ll be checking here regularly so don’t get any ideas.

I was stunned to feel the emotion rise and tears flow—as if I was actually burying an old friend—which I was. We cooked burgers and swam in the pool and told war stories and laughed—and cried—a little more.

The entire process was very healing.

With apologies to any of my readers named Larry. I didn’t know why The General had called me Larry that particular day in the mid-90s. When I asked him years later, he said it was something he said to guys who had gotten way out over their skis. It stuck to me like a summer sweat.

I’m forever grateful to my friend. He gave me a persona—a Mr. Hyde—that I could one day murder and bury.

What a powerful process to engage in. The name, the letters, the funeral make saying good-bye so much more tangible. Thank you for sharing this excellent tool.

25 years ago at a friend's wedding the name plate that marked my seat at the table said, "Lush". It took me 20 years to realise that that nickname weighed far heavier on the sad side of the humour see-saw than on the funny side. Lush is dead and buried now too. I'm not angry with her. She was sad and clueless and the worst harm she did was to herself. I hope Larry and Lush are looking down on us now and feeling secretly proud of us for surviving them.