Readers, you’ll find my own essay and contribution to this collective effort just below this brief introduction.

As you may or may not have seen, this last week a group of six men have written essays on Fatherhood. My contribution, here today, is the 6th in the series. I hope you’ll read and follow these terrific men and writers—linked below—on your own. Not all of us are fathers ourselves, but each of us have been deeply and profoundly challenged by the questions around, and the impact of, fatherhood. We decided as a group to choose this first theme to write about separately and in harmony. God willing and the creek don’t rise, there will be more topics to dig into together—as men.

Enjoy. If you like what you read, please consider subscribing, commenting with your own reflections, and of course, sharing. These men are the 6 essay writers undertaking this topic.

You may read each of the essays individually by following this link to our fearless leader Bowen Dwelle’s cumulative introductory post.

Now my essay on fatherhood, entitled “Fatherhoodlessness”

What do I know about it? A lot. What do I know about doing it? Nothing. Indulge me.

I always thought I’d father a bunch of kids. Always wanted to. I grew up imagining myself having kids.

The concept of an early marriage to my college sweetheart with a bunch of kids running around the yard after their teacher Mom and coach Dad came within reach of my grasp in my final two years at SMU. We’d been together for a couple of years and were madly in love. She went to an 8-week Christian camp the summer after my senior year/her junior. Letter correspondence that summer didn’t indicate anything changing, but when I picked her up for the 9-hour drive home at the end of camp, my world fell apart.

“I’m in love with Jesus Christ and I can’t be in love with you at the same time.” This was in about hour number four—so halfway home. We’re two feet from one another in the car. Nowhere to go. Must listen. Can’t run. I’m driving. And my insides are melting as she explains her feelings to me. “Tell me what you’re feeling. Say something,” she says.

Screw you God. Screw you Jesus. How about that? How ‘bout fuck you and that stupid camp and all those ideas they put in your head. I didn’t verbalize any of those feelings. Instead, I said quietly, “I love you. I love Jesus too. I don’t see any conflict with that. I think you’re confusing your feelings, and this will all be fine with time.” Yeah—when I get you back home and naked in bed and away from those God squad nut cases you’ve been with all summer.

What’s the connection between this story of my young broken heart and an essay on Fatherhood? Simple. This first great love was as close as I ever got. A great love spurned and burned evolved into a great bitterness. I was a bachelor—and a budding alcoholic—on a mission to consume love and attention while investing a minimum of my own. In those years I participated in aborting a life that I’d helped create. Regret and shame from that decision surfaced many years later in counseling during my recovery.

Career choices made in those early years also didn’t support raising a family. I traveled like a carnival vendor in my 30s and into my early 40s in the sports television business—gone 46 weekends a year out of 52. The saying “a ship in every port” wouldn’t be far from the truth in describing my relationship status. There were a couple of meaningful relationships—even shared a home with one of my loves. But I was gone. All the time. I couldn’t see fatherhood on the horizon because I really couldn’t welcome marriage.

So, what do I actually know about fatherhood? Sitting at breakfast today with several loved ones, I was reminded that one key difference between motherhood and fatherhood is the level of biological investment—that a woman can’t possibly know what it’s like to be a mother without having had a child. Whereas a father’s duties could be assumed and performed and understood more easily. I’m not sure. But I do know that I have witnessed both wonderful and despicable examples of fatherhood up close and personally.

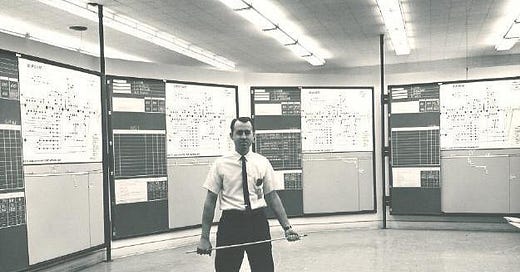

My own father, who I’ve written about a few times but none more than in my Father’s Day tribute this year, had a heart attack at age 60. He’s now 88. My Dad was my constant companion and also my coach. As his first son, he was constantly teaching me the skills of all the major ball sports. I became an above average football, basketball, and baseball player—advanced for my age compared to nearly all of my peers. Attentive and present in my younger years, my father largely disappeared from that role due to career demands as I entered my teenage years. Most of my game performance memories include Mom in the stands, while Dad was in an office or a hotel far away, or on a corporate jet going or coming back from somewhere. When my Dad did show up for a game, what I remember is the intense pressure to perform—which wasn’t a normal feeling when he wasn’t around.

It was only in my recovery and counseling sessions decades later that I began to understand and deal with the profound sense of loss and abandonment I had felt at the time. I know now—but didn’t understand at the time—that much of my acting out and my rebelliousness stemmed from this need for his attention—through whatever means.

My father was a powerful man and a palpable presence. I lived my life, on and off the field of play, attempting to win his love and foster his sense of pride in me. I’m sure he felt both of those feelings, but my Dad, like many men of his generation, struggled with expressing those emotions outwardly and verbally. So I searched—and was left wanting.

I remember getting the phone call from my younger brother on Christmas Day 1995. My parents were visiting my brother’s home in Dallas for the holiday week. I was skiing with my girlfriend and her family in Vail—my home at the time. My early model Motorola cellphone had zero coverage in the back bowls of Vail and remained tucked away deep in a pocket of my Descente vest. It was only when I reached the bottom of the mountain at the end of the day that I got the message. “Dad had a heart attack at the kitchen table following a Christmas morning run around the neighborhood He’s alive and in the hospital in Plano.”

I immediately dug into my plentiful United Mileage Plus account for a flight to Dallas. I was able to make it there the next morning. I stayed for a week and ended up driving my maternal Grandmother Polly back to Arizona in my Dad’s car. My gig at the time was as on-site race announcer and co-producer for the US Professional Ski Tour on ESPN. Miraculously, I had a couple of weeks respite before I had to be in Squaw Valley, California in mid-January. I have many memories of that week. I remember that my Dad had zero short term memory of the event—to this day. I would walk out of the hospital room for a coffee or a quick pee, leaving my brothers and my Mom there. When I’d return my Dad would look at me and exclaim “Dee what are you doing here?” I’d been with him for the last couple of days and he couldn’t remember me being in the room 10 minutes ago. I vividly remember the soft, loving look on his face as he laid eyes upon me—for the first time he thought—for the 20th time in several days. My Dad was vulnerable and emotionally transparent. It was something I’d never seen before those moments in the hospital room. He had always seemed so strong—larger than life. It shook me to my core, but it also endeared me in a way that was unrecognizable. My hero—my rock—on his back unable to fill out the Superman suit I’d always seen him in.

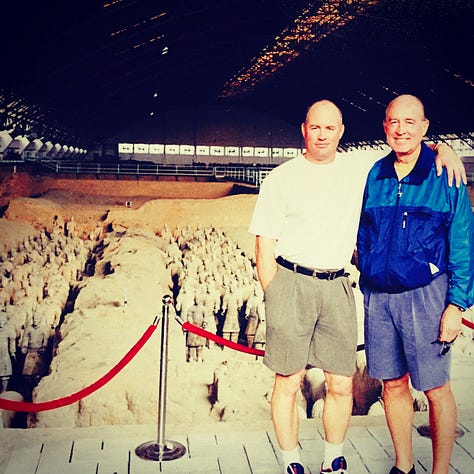

One of my Father’s memorable life corrections following the remarkable recovery from his heart attack was to invest in a mandatory family reunion every other Christmas. We’ve now done it 13 times in the 28 years hence. All of these events were at my parents’ expense and all of them were at amazing destinations. Each of our lives henceforth have been enhanced by this gift of generosity from my parents. One direct outcome of these gatherings, and also of the many Father/Son golf outings we made together, was to build a bridge to my father. The time—with a new understanding of the fact that we were all on borrowed time—helped me understand what his commitment to his children meant, and to know that he and my Mother were doing the absolute best that they knew how. I learned forgiveness, and I learned to pivot from fear and respect into acceptance and love.

Father figures have been important in my life. Two that stand out were from high school. Both taught me things that I didn’t fully recognize until much later. One was my high school basketball coach Dawson Pike. A quiet and stoic leader of young men, he encouraged me without hesitation to broaden my life experience by quitting the team my senior year to play the lead in our school’s musical that year. The other was on the receiving end of that decision of mine; Dr. Charles Prokasky, the choral director at our school who first tempted me to take on the singing role of Curly in “Oklahoma.” The only prerequisite was that I had to drop out of being the point guard for our returning 29-3 Missouri State Championship runner-up basketball team. Both men taught me fearlessness—just as a father might. I write about this decision in the same Father’s Day essay referenced above.

Each of my two brothers raised two daughters. At a point in their young lives, both men took sabbaticals from their lucrative corporate careers to spend more quality time as dads. It shows. All four of my nieces are wonderful young women with a solid foundation of sound and reasonable thinking courtesy of a loving and present two-parent household.

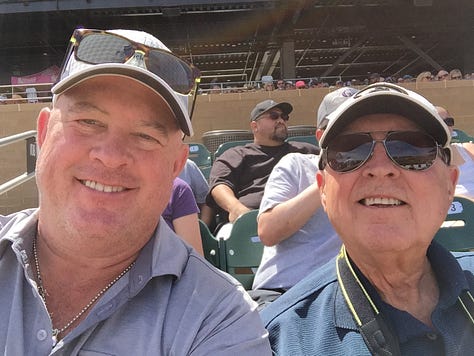

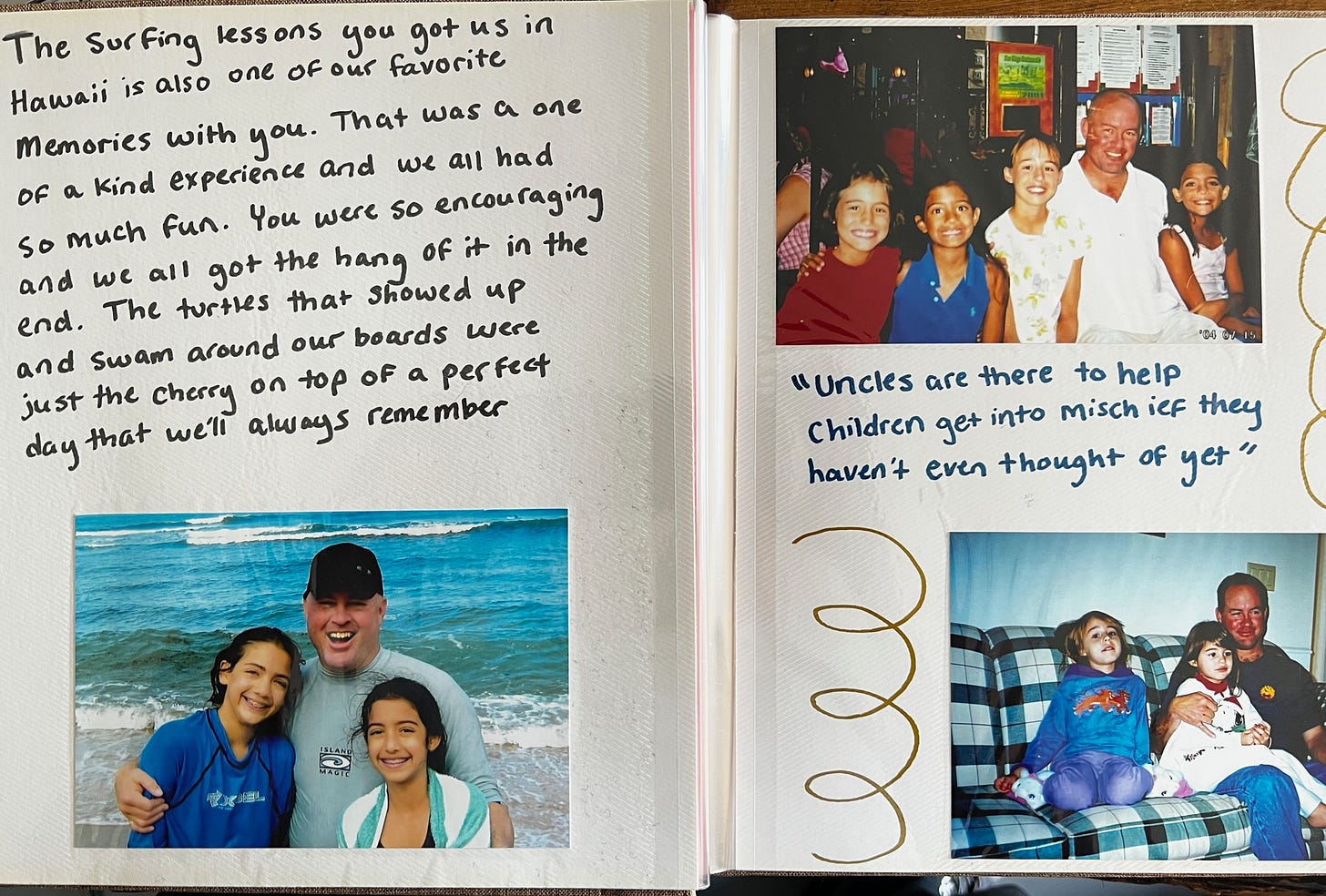

I have tried to be a loving and highly engaged uncle in the lives of each of these fine young women. On our most recent family gathering a few years ago in Coronado, my four nieces took me aside and presented me with a lovingly constructed picture and prose scrapbook. The personal messages from each of them, and the photos contained within represented their pride in me for my recovery journey, and in my investment in their young lives as their uncle. I was beyond moved. It is one of my most treasured possessions.

I have had the wonderful experience of being “Uncle Dee” to the children of many of my close friends, teaching them how to throw and catch—giving them a sense of manhood from a different perspective to supplement what their own fathers—my good friends—might provide. I have since lost a couple of those friends much too early, and I still maintain a relationship with their sons and daughters.

These loving relationships—while not replacing the experience of raising my own children—have added richness and meaning to my life. All of these close examples of wonderful fathers both within and outside my nuclear family were positive and loving ones.

As a part of my journey through addiction and recovery, I’ve also seen despicable examples of parenting by fathers. Neglect, abuse, mistreatment, abandonment, and heartbreaking tragedy. These tragic fathers’ lives were very likely set in motion by trauma or abuse in their own young lives. Both trauma and addiction—particularly in alcoholism—are generational within families. Not because of biology—there hasn’t been any scientific research supporting an addiction “gene” although laymen might claim it now and then. The perpetuation of addiction in families is based entirely upon learned behaviors and narratives and trauma that is passed on from fathers and mothers to sons and daughters.

Is it better for a child to not have a father, or to have a father that is abusive? Circular question requiring much more dialogue. Prisons and treatment centers and morgues are full of young men of both experiences. Dr. Gabor Mate is a renowned and somewhat controversial expert on trauma, and he speaks about the “little Ts” of shame and slight and disappointment as being as equally impactful on young people as the “big Ts” of violence and abuse. Maybe more so due to their quiet and insidious nature.

I believe the evidence indicates that one of the key parenting measures today involves monitoring the use of social media. It’s clear that this online environment has caused great harm to our young people that have grown up with it. Kids who represent otherwise healthy lives on the outside can nonetheless have secret second lives of anger, FOMO, anxiety and depression in their online lives. I don’t know how to effect change in this area as a non-parent, but I do know that social media can be as devastatingly addictive as any other substance.

Through my recovery, I’ve invested time, treasure, and professional expertise to the Children’s Program of Hazelden Betty Ford. This unique and powerful workshop program was designed by Betty Ford herself and addresses the specific trauma and emotional burdens borne by the children of alcoholics and addicts. I know the percentages. They’re not good. The cycles must be broken somewhere in the family tree. In my soul, I’m grateful to be here, after the debilitating years of self-destructive behavior.

To put a sharp point on this entire reflection on fatherhood: my father is the only one person in the entire universe who could have pulled off my effective intervention on Nov 23, 2009. God, my friends, my other family, my business partners, my lovers—had all tried. Only my Dad could reach deep into my gut full of shame and command me to take the next right action. And he did. And I am—recovered.

One related aspect of my life experience in fatherhood is as a pet rescuer and dog dad. I’ve “parented” 8 dogs in my adult years: 6 rescues and 2 pedigreed purebreds. Most of this time was as a single parent. Only in the last few years has our family expanded to include the love of my life, Ann, who has loved and welcomed four 70+ pound beast mutts into our life together. None of my dogs has ever spent time in a kennel, with two exceptions at a luxury ranch pet resort in AZ. Most always they have a full time in-house dogsitter and have remained in their own homes and beds while I’ve been away traveling. They have hiked to the top of 14,000-foot peaks in Colorado, taken cross-country road trips, slept in my bed, swum daily in my pools, and accompany me everywhere. They have all been spoiled relentlessly. The soaring joy and the unmatched grief of pets who love unconditionally without expectation or resentment is unique and known to all who have had the experience.

In summary, I’ve had powerful experiences of fatherhood while never having been a father. I feel privileged to be able to weigh in on the subject at all. Not every man gets to be a father. I think I would have been a good one. But it may have taken me awhile to grow into it. Who knows? Life deals us opportunities to make choices—that is our only guarantee. On this day, I still have the sound of my father’s voice in my head from my younger years, but softened by the life experiences, a new understanding, and the solid bridge built between us in the years since then. What an incredible gift.

Thanks Latham. After reading y’all’s I knew I had to take the bar higher. ☺️

I appreciate your words about my essay. I found your essay so incredible and thought-provoking. Can’t wait for the next group theme project. 🙏

Thanks Bowen! So psyched to be a part of the group.

I’m taken by your comments on OPKs and parents knowing more somehow.

You need a license to drive but there’s no qualification for parenting. You just suddenly are one. Some are good at it...many aren’t. I guess it’s like anything else, you’re good at what you direct your focus on. Many people are chronically distracted in life and therefore in parenting as well. No judgement. It is what it is: life.